Abstract

Moderation of online User Generated Content (UGC) is a relatively recent profession. Content moderation professionals, time to time, flag and take down objectionable content on the Internet to ensure it is safe and secure place for everyone. In the same spirit, the Amigo Circle Mentoring Program was conceptualized at Wipro to provide a safe space for content moderators to meet, share experiences and issues, and learn techniques to maintain positive well-being. The Amigo Circle adapts to the structure of Employee Resource Groups (ERGs) and mentoring programs to tap into the therapeutic value of informal peer groups and protect psychological well-being.

The Amigo Circle consists of self-nominated, experienced Champs trained by mental health professionals to facilitate the Amigo Circle meet-ups. The colleagues of the Champs are collectively called Amigos.

We have conducted a study to investigate the effectiveness of the Amigo Circle. Using the program, we investigated the differences in well-being scores among employees who were a part of the Amigo Circle compared to those who were not.

We conducted exploratory analyses on the feedback from members of the Amigo Circle on the program’s effectiveness. Several promising trends were found. Members of the Amigo Circle had lower scores in depression, anxiety, and stress obtained from the DASS-21 compared to a control group of non-members. A higher percentage of the Amigo Circle members reported they had someone to talk to when stressed than non-members. Additionally, there was positive feedback on the program. More than 80% of members reported a greater sense of belongingness and reported that the Amigo Circle had helped them become more aware of their thoughts and feelings, ultimately making it comfortable to talk about well-being. A similar positive sentiment was reflected in the word Cloud derived from the written feedback provided by members. Overall, the Amigo Circle program succeeded in enhancing mental well-being by having moderators openly discuss well-being issues to help overcome any stigma, shame, and secrecy around mental well-being, become more aware of one’s thoughts and feelings, and develop a sense of belonging to the organization through connectivity with colleagues.

Introduction

In the light of fostering a culture of psychological well-being in organizations, the Amigo Circle (i.e., circle of friends) was conceptualized to bring together employees who share similar experiences and familiarity with work. More specifically, the Amigo Circle was created for employees in the content moderation space. This circle was intended to allow employees to freely express their thoughts and views about the nature of their work, with the comfort of facilitation done among themselves. The Amigo Circle leverages the therapeutic value of informal peer groups to protective emotional well-being at large. The Amigo Circle is structurally similar to many informal ERGs and mentoring programs.

Employee Resource Groups and Organizational Mentoring

ERGs or affinity groups have existed for over 60 years (1960s; Douglas, 2008[1]). ERGs are voluntary, employee-led groups with employees going beyond their core jobs to be a part of the group. ERGs provide social and professional support and avenues for information sharing (Wellbourne et al., 2015; Kravitz, 2008; McGrath & Sparks, 20052). ERGs are sponsored mainly by the organization but are created based on employee needs. They adopt a bottom-up approach to the need being addressed.

Welbourne and Leone McLaughlin (2013) identified three overarching types of ERGs:

ERGs are becoming more prevalent in Fortune 500 and mid-sized companies due to their benefits at the organizational and employee level (Wellbourne et al., 20153). Examples of organizational benefits include fostering racial inclusion, bridging cultural differences, and boosting the company’s reputation (Kaplan et al., 20094). As for employee-level benefits, it was found that mentoring within the ERG contributes to a positive outlook for black managers regarding their careers (Friedman et al., 1998). ERGs have been shown to improve communication within and across groups, aid in honing problem-solving skills and professional development, and build a culture of trust and community (McGrath & Sparks, 2005; Welbourne & Ziskin, 2012; Van Aken et al., 19945).

Organizational mentoring programs have also shown similar benefits. Mentoring involves a dyadic relationship in which the mentor shares and disseminates wisdom or knowledge to the mentee (Bozeman & Feeney, 20076). A friendship is built over a level of commitment and trust where both the mentor and mentee can share their opinions, views, and experience with each other without the fear of passing judgment (Carter & Youssef-Morgan, 2019; Kram, 1988; Kram & Isabella, 1985; Pettinger, 20057). This arrangement has proven to provide emotional support and career advances as well as influence job performance (Carter & Youssef-Morgan, 2019; Ingram & Roberts, 20008).

Despite the rising prevalence of ERGs and mentoring practices in organizations, there is an underwhelming amount of research investigating the impact of ERGs on individual psychological well-being, especially in organizations (Wellbourne et al., 20159) and more so in the Online Trust and Safety space of content moderation.

Conceptualization of the Amigo Circle

As a profession, moderation of online User Generated Content (UGC) exists in a gauzy, grey zone. The job of content moderators is to flag objectionable content or take it down, is not easy. However, they keep at it, making the Internet a safe and useful space for everyone. Content moderation is still nascent, and there is limited evidence-based data and research published on this work's impact on employees' well-being. We can, however, draw on the extensive research available in other occupations that deal with secondary stress or vicarious trauma, which is triggered by direct or indirect exposure to someone else’s trauma.

Content moderation is a relatively new profession. Few understand the nature of the work or how it affects moderators’ well-being. The moderators cannot discuss workplace-related issues with their friends and family the way most of us usually do. Many cannot discuss the impact of emotional distress from monitoring inappropriate content as societal stigmas around mental well-being are still prevalent. Naturally, they feel isolated—a condition made severely acute by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many moderators often seek workplace support. Wipro recognized this need. In 2020 the Amigo Circle program was launched to provide moderators with a safety valve.

The Amigo Circle provides a safe, non-judgmental space where discussions are kept confidential (unless a professional mental health intervention is needed). The Amigo Circle aims to have moderators openly discuss well-being issues, overcome any stigma, shame, and secrecy around mental well-being, develop a sense of belonging, work off any issues, and obtain psychoeducation on enhancing and maintaining positive well-being levels. This is expected to allow moderators to continue working, demonstrating optimal efficiency and judgment that their job demands.

Structure of the Amigo Circle

The structure of the Amigo Circle is similar to the structure of an ERG and organizational mentoring.

Each Amigo Circle consists of a Champ and several Amigos. Champs are self-nominated employees who have spent at least six months as a moderator and understand the challenges of the job. These Champs are trained to help moderators (whom we call Amigos), who are also colleagues, maintain balance by functioning as empathetic sounding boards. Mental health professionals train the Champs in mentoring skills, empathy, active listening, and destigmatizing mental health. Champs maintain regular connects with these professionals for continual psychoeducation that can be shared with the Amigos. The current Champ to Amigo ratio is 1:9. The Champs and the Amigos meet on a fortnightly basis. Amigos use the meetings to voice their concerns and share their experiences. The Champs facilitate these discussions and impart knowledge on relevant coping techniques everyone can practice – for example, mindfulness, grounding exercises, journaling, etc.

Investigating the Effectiveness of the Amigo Circle

We have conducted a study to investigate the effectiveness of the Amigo Circle. Using the program, we investigated the differences in well-being scores among employees who are part of the Amigo Circle compared to those who are not. We also obtained feedback from the Amigo Circle members on the program's effectiveness.

It is hypothesized that employees who are a part of the Amigo Circle would have better well-being scores compared to employees who are not a part of the Amigo Circle. We expect to observe this phenomenon due to several reasons. First, the Amigo Circle may pose as a social support network. The reciprocal relationship developed among its members would foster a sense of belonging and thus promote greater well-being levels (Hammell et al., 201410). Second, applying the dyadic exchange dimension of social exchange theory (Homans, 197411), a mutual commitment would arise among the members to break the 3s’ – stigma, shyness, and secrecy – around discussing mental health. This would promote recognizing, discussing, and resolving any potential issue. Third, according to resource theories (Kram, 198512), the Amigo Circle would provide the resources to enhance psychological well-being. The feedback data was intended to understand whether the aforementioned factors were the underlying reasons that enhanced well-being levels. Thus, an exploratory analysis was conducted on the feedback data to further understand the impact of the Amigo Circle.

Methodology

Participants

The Amigo Circle program comprised 312 employees (32 Champs and 280 Amigos). Our well-being surveys were voluntary to complete. We obtained well-being data from 182 employees (20 Champs and 162 Amigos). A location/work-process matched control group of 182 non-Amigos was identified among employees who had completed the well-being survey.

Measures

Well-being scores

Well-being was conceptualized as the scores of depression, anxiety, and stress from the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21). DASS-21 is a 21-item self-report instrument measuring the aforementioned three related negative states. The DASS-21 has sound psychometric properties with strong reliability and validity (Norton et al., 200713).

Additionally, we looked at the percentage of Amigos versus non-Amigos who reported whether they had someone to talk to when stressed.

Feedback Data

Feedback forms were given to members of the Amigo Circle. The form was designed to measure the level of belongingness, level of comfort in discussing well-being matters, whether the individual is more aware of their thoughts and emotions because of the Amigo Circle, and how much they look forward to these sessions.

Champs were also asked whether they saw Amigo Circle as an opportunity to help their colleagues, take on leadership roles, positively impact their colleagues, and help others become more comfortable discussing well-being matters.

Amigos were additionally asked if their needs were recognized and addressed, about the satisfaction of their relationship with the Champs, and if they feel the organization cares about their well-being.

Lastly, Champs and Amigos were asked to provide written feedback on how the Amigo Circle had helped them.

Analyses

An independent sample t-test was conducted to assess if DASS-21 scores were different among Amigos and non-Amigos. Non-parametric alternative to the independent sample t-test (Man Whitney test) was conducted to determine if a higher number of Amigos reported they had someone to talk to when stressed compared to non-Amigos. Exploratory analysis was conducted on the feedback survey data. Lastly, a word cloud was obtained based on the keywords from the written feedback using the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK; https://www.nltk.org/) with Python.

Results

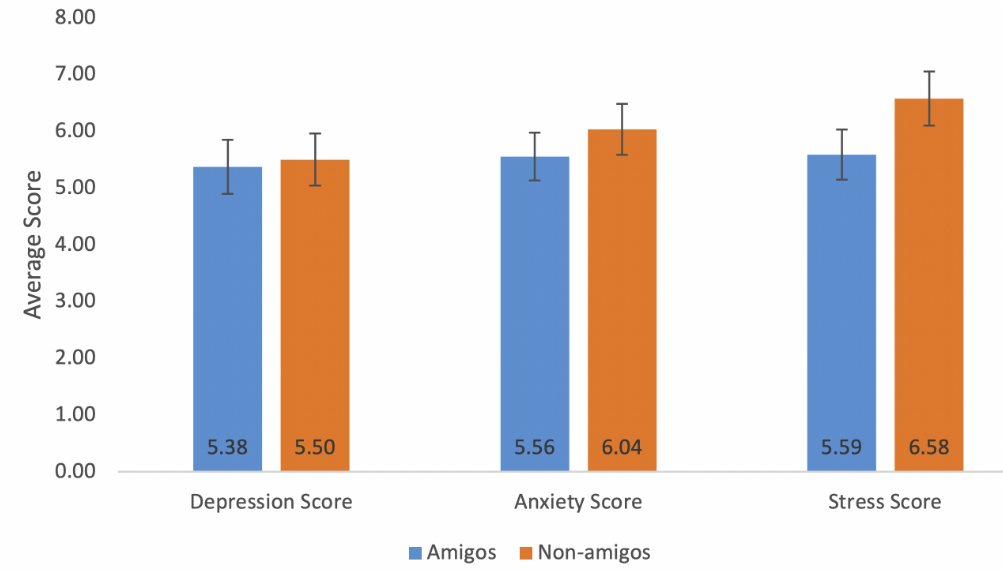

Both, members of the Amigo Circle, Amigos and non-Amigos (the control group), are in the normal range of scores for depression, anxiety, and stress. Although both groups are in the normal range, Amigos had lower scores in depression, anxiety, and stress compared to non-Amigos (refer to Figure 1); Depression: Amigos – 5.38 ± 0.48, Non-Amigos – 5.50 ± 0.46; Anxiety: Amigos – 5.56 ± 0.42, Non-Amigos – 6.04 ± 0.45; Stress: Amigos – 5.59 ± 0.44, Non-Amigos – 6.58 ± 0.48; tDepression = -0.20, tAnxiety = -0.78, tStress = -1.52, p > 0.001. This trend favors our postulate.

Figure 1 shows Amigos have lower scores in depression, anxiety, and stress compared to non-Amigos, as obtained from DASS-21 scores

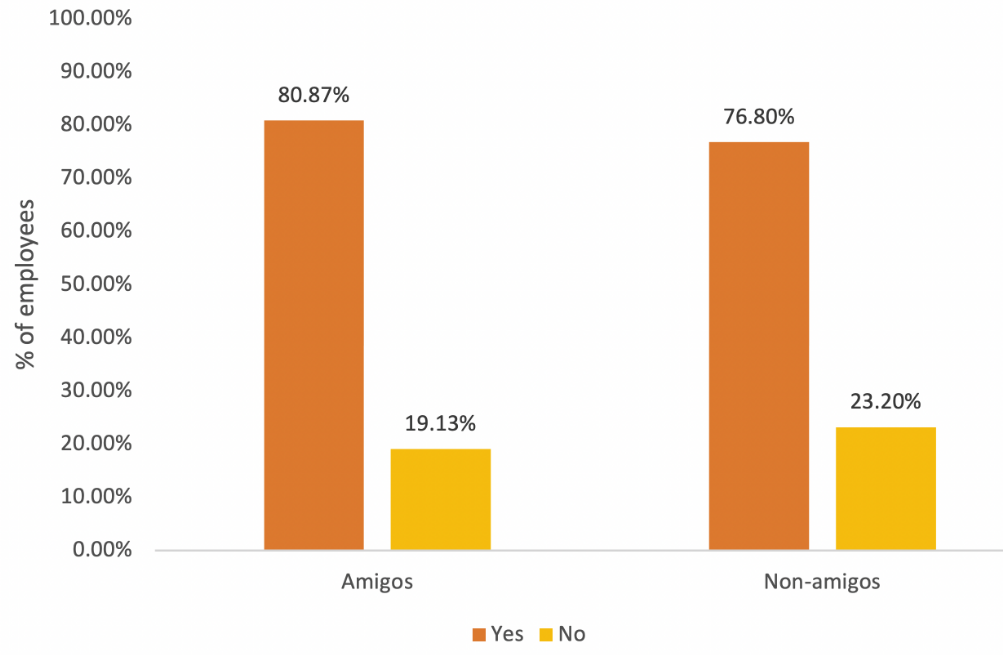

Additionally, a higher percentage of Amigos (80.87%) reported they have someone to talk to when stressed compared to non-Amigos (76.80%; refer to Figure 2); tMannWhitneyU = 15886, p > 0.001. Again, this trend is in line with what we expected.

Figure 2 shows that a higher percentage of Amigos have someone to talk to when stressed compared to non-Amigos

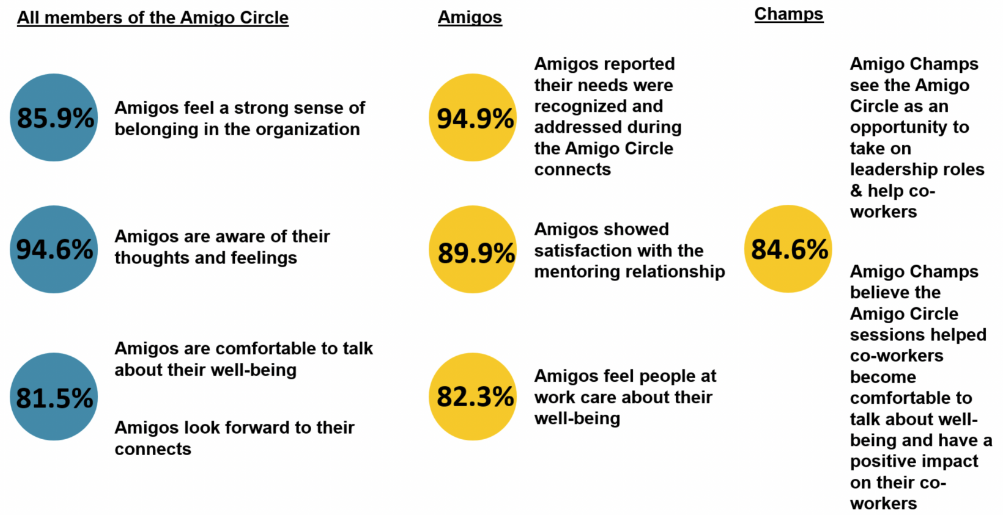

An infographic of the findings from the exploratory analysis of the feedback data is provided (Figure 3). Overall, the feedback showed that the employees received the Amigo Circle positively.

Figure 3 shows positive feedback for the Amigo Circle program from its members

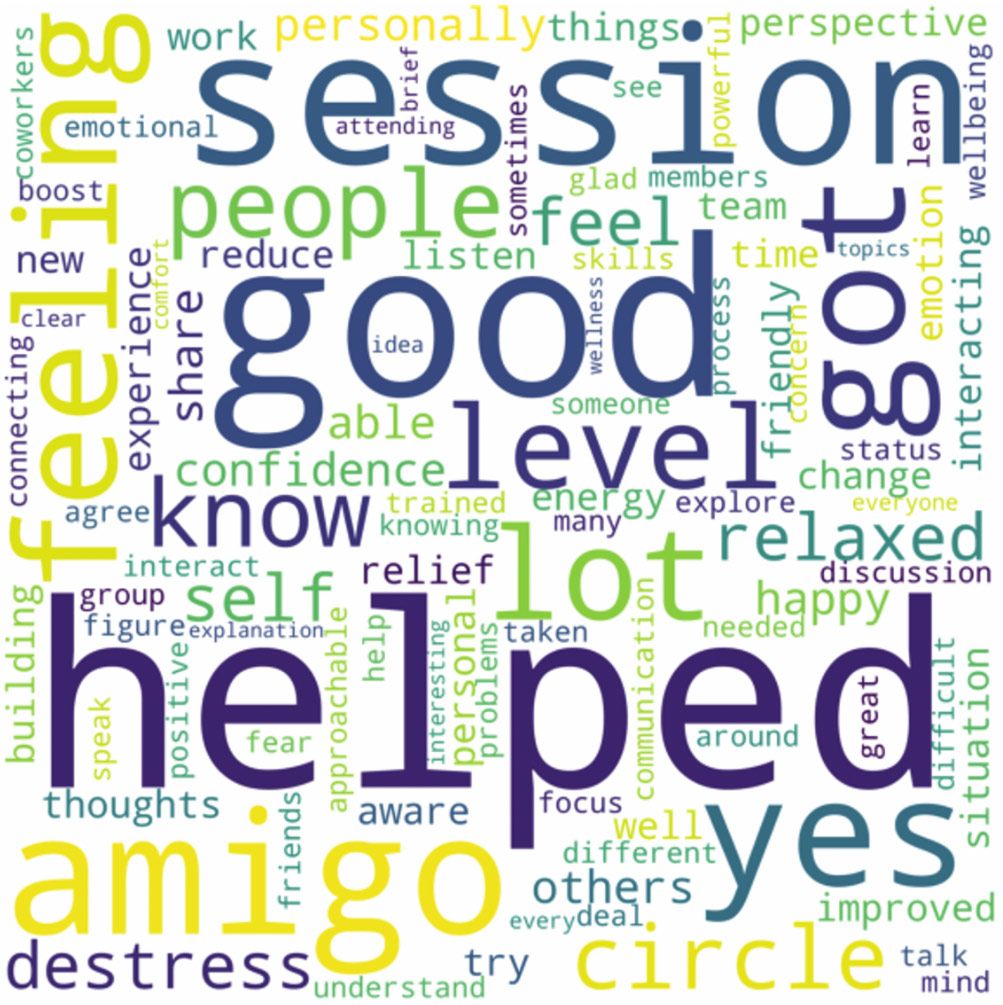

The word cloud of the feedback highlighted many positive comments on how the Amigo Circle had helped its members (Figure 4). Keywords such as helped, distress, good, relaxed, aware, improved, positive, approachable, etc., dominated the feedback.

Figure 4 reflects the positive feedback on how the Amigo Circle has helped its members

Discussion

This study investigated the effectiveness of the Amigo Circle program. The Amigo Circle program was conceptualized to provide content moderators of the online UGC a safe space to gather employees who share similar experiences and have work familiarity. The Amigo Circle consists of self-nominated, experienced (in content moderation) Champs trained by mental health professionals to facilitate the Amigo Circle meetups. Their colleagues form the Amigos. The Amigo Circle taps into the therapeutic value of informal peer groups, mainly ERGs and mentoring programs, and acts as a protective layer to promote psychological well-being. The goal of the Amigo Circle is to have moderators openly discuss well-being issues, overcome any stigma, shame, and secrecy around mental well-being, develop a sense of belonging, work off any issues, and obtain psychoeducation on how to enhance and maintain positive well-being levels. This is expected to allow moderators to continue demonstrating optimal efficiency and judgment in their job demands.

As hypothesized, compared to the work process and location-matched control group, the Amigo Circle program members had lower scores in depression, anxiety, and stress measures collected using the DASS-21. Although this difference was not statistically significant, the trend looks promising as it reflects that the program may enhance well-being levels. Additionally, supporting the program’s effectiveness was a trend that found a higher percentage of members reporting they had someone to talk to when stressed compared to non-members.

Feedback data was obtained to understand the potential underlying factors that promote well-being levels among members of the Amigo Circle. Several important findings were obtained from the exploratory analyses of the feedback data.

First, it was found that approximately 85.9% members reported they felt a strong sense of belonging to the organization, 81.5% reported they looked forward to their connects, and 89.9% showed satisfaction with their mentoring relationship. These findings lend substantial support to the conjecture that the reciprocal relationship that would have developed among members of the Amigo Circle would foster a sense of belonging. Being a part of the Amigo Circle gives access to a social support network where members can discuss anything from work-related to person-related matters in a safe, non-judgmental environment. Thus, a greater sense of belonging to such a social support network would promote greater well-being; a common phenomenon found throughout the literature (for example, see Hammell et al., 201414)

Second, 81.5% of members reported being comfortable talking about well-being, and 94.6% reported being aware of their thoughts and feelings. This corroborates the notion that the Amigo Circle program aids in overcoming the 3s’–stigma, shyness, and secrecy–around discussing mental health issues. Additionally, it was seen that 94.9% of the Amigos reported that their needs were recognized and addressed during their meetings. This validates our notion that the Amigo Circle program promotes recognizing, discussing, and resolving any potential issue.

The abovementioned findings may be explained by applying the dyadic exchange dimension of social exchange theory (Homans, 197415). According to this theory, well-being may be enhanced through reciprocity between the Champs and the Amigos. Amigos may feel indebted to the Champs’ investment in providing a safe space to discuss anything and psychoeducation. Thus, as a tangible return to the Champs’ investment, Amigos are motivated to reciprocate by fully using their sessions and working on their well-being. Another view of the social exchange theory is that with continual interaction over time, obligations are generated through mutual commitments (Emerson, 196716). Applied to the current situation, the obligation would be the continual effort to look after their well-being levels. Champs invest time, energy, and other resources in obtaining the training and knowledge to facilitate and impart relevant psychoeducation skills during the Amigo Circle sessions for social, economic, or political gains. Here, 84.6% of Champs see the Amigo Circle program as an opportunity to take on leadership roles (political gain) and positively influence their fellow Amigos by enabling them to be comfortable talking about their well-being (social gain). Amigos perceive people at work to care about their well-being (as reported by 82.3%), thus staying motivated to work on their well-being levels. Overall, this process allows all members of the Amigo Circle, both Champs and Amigos, to pay greater attention to maintaining positive well-being levels, often reflected in their well-being scores.

Lastly, according to the resource theories (Kram, 198517), the Amigo Circle would provide the resources to enhance psychological well-being. This notion is supported by our findings from the word cloud designed from the keywords from the written feedback by members on how the Amigo Circle helped them. Words such as helped, good, distress, relaxed, feeling, improved, etc., underline how the Amigo Circle program was resourceful in promoting well-being.

All trends among Amigos compared to non-Amigos were in line with the hypotheses, but they did not reach statistical significance. One plausible reason for not reaching statistical significance could be the nature of the control group. The control group was identified by matching only the work-process and location of work. In future, age should also be factored in so that the control group becomes work process, location, and age. Age could be a potential protective factor for well-being levels, with older people having greater levels of well-being (for example see Leeann Mahlo et al., 202018). For future research, different measures of well-being can be assessed to see if the Amigo Circle has greater well-being levels. For example, the professional quality of life questionnaire could measure compassionate satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. Another measure could be resilience levels. Regardless, the trend where members of the Amigo Circle have lower depression, anxiety, and stress scores shows that the Amigo Circle program adds an extra layer to promote greater well-being.

Conclusion

Findings from this study point toward the potential benefits of the Amigo Circle program. Members of the Amigo Circle program have greater well-being levels compared to non-members. The study also identify potential underlying factors driving an individual’s well-being levels – mainly, the well-being benefits due to a greater sense of belonging to a social support network, the development of a mutual commitment among the members to break the 3s’– stigma, shyness, and secrecy – around discussing mental health issues. This would promote recognizing, discussing, and resolving any potential issue. Lastly, the Amigo Circle provides the resources to enhance psychological well-being.

References

1. Douglas, P. H. (2008). Affinity groups: Catalyst for inclusive organizations. Employment Relations Today, 34(4), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/ert.20171

2. Kravitz, D. A. (2008). THE Diversity–Validity Dilemma: Beyond Selection—The Role Of Affirmative Action. Personnel Psychology, 61(1), 173–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00110

3. McGrath, R., & Sparks, W. L. (2005). The importance of building social capital. Quality Control and Applied Statistics, 50(4): 45-49.

Welbourne, T. M., Rolf, S., & Schlachter, S. (2015). “Employee Resource Groups: An Introduction, Review and Research Agenda.” Academy of Management Proceedings, 2015(1), 15661. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2015.15661abstrac

4. Welbourne, T. M., Rolf, S., & Schlachter, S. (2015). “Employee Resource Groups: An Introduction, Review and Research Agenda.” Academy of Management Proceedings, 2015(1), 15661. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2015.15661abstract

Kaplan, M.M., Sabin, E., & Smaller-Swift, S. (2009). The Catalyst Guide to Employee Resource Groups. Volume 1: Introduction to ERGS.

5. McGrath, R., & Sparks, W. L. (2005). The importance of building social capital. Quality Control and Applied Statistics, 50(4): 45-49;

Welbourne, T.M., & Ziskin, I. (2012). Employee resource groups as sources of innovation. Presented at the 2012 ERG Conference.

Van Aken, E. M., Monetta, D. J., & Scott Sink, D. (1994). Affinity groups: The missing link in employee involvement. Organizational Dynamics, 22(4), 38–54.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(94)90077-9

6. Bozeman, B., & Feeney, M. K. (2007). Toward a Useful Theory of Mentoring. Administration & Society, 39(6), 719–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399707304119

7. Carter, J. W., & Youssef‐Morgan, C. M. (2019). The positive psychology of mentoring: A longitudinal analysis of psychological capital development and performance in a formal mentoring program. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 30(3), 383–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21348

Kram, K. E. (1988). Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. Lanham, MD: University Press of America

Kram, K. E., & Isabella, L. A. (1985). Mentoring Alternatives: The Role of Peer Relationships in Career Development. Academy of Management Journal, 28(1), 110–132. https://doi.org/10.5465/256064

Pettinger, L. (2005). Friends, Relations and Colleagues: The Blurred Boundaries of the Workplace. The Sociological Review, 53(2_suppl), 37–55.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954x.2005.00571

8. Carter, J. W., & Youssef‐Morgan, C. M. (2019). The positive psychology of mentoring: A longitudinal analysis of psychological capital development and performance in a formal mentoring program. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 30(3), 383–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21348

Ingram, P., & Roberts, Peter W. (2000). Friendships among Competitors in the Sydney Hotel Industry. American Journal of Sociology, 106(2), 387–423. https://doi.org/10.1086/316965

9. Welbourne, T. M., Rolf, S., & Schlachter, S. (2015). “Employee Resource Groups: An Introduction, Review and Research Agenda.” Academy of Management Proceedings, 2015(1), 15661. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2015.15661abstract

10. Hammell, K. R. W. (2014). Belonging, occupation, and human well-being: An exploration. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 81(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417413520489

11. Homans, G. C. (1974). Social behavior: Its elementary forms, Revised ed. (p. 386). Oxford, England

12. Kram, K. E., & Isabella, L. A. (1985). Mentoring Alternatives: The Role of Peer Relationships in Career Development. Academy of Management Journal, 28(1), 110–132. https://doi.org/10.5465/256064

13. Norton, P. J. (2007). Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21): Psychometric analysis across four racial groups. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 20(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701309279

14. Hammell, K. R. W. (2014). Belonging, occupation, and human well-being: An exploration. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 81(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417413520489

15. Homans, G. C. (1974). Social behavior: Its elementary forms, Revised ed. (p. 386). Oxford, England

16. Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social Exchange Theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2(1), 335–362. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.02.080176.002003

17. Kram, K. E., & Isabella, L. A. (1985). Mentoring Alternatives: The Role of Peer Relationships in Career Development. Academy of Management Journal, 28(1), 110–132. https://doi.org/10.5465/256064

18. Mahlo, L., & Windsor, T. D. (2020). Older and more mindful? Age differences in mindfulness components and well-being. Aging & Mental Health, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1734915

Bindiya Lakshmi Raghunath

Bindiya Lakshmi Raghunath is the Global Research Analyst for Wellbeing and Resilience, for the Consumer Business Wipro-iCORE. She brings her expertise in social, affective, and cognitive neuroscience to understand and consequently develop evidence-based approaches to promote employee wellbeing, grounded by the biopsychosocial framework. Bindiya is a graduate from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, with a decade of experience in human behavioural neuropsychology research. She has various publications in scientific journals, presented across various international conferences, and delivered numerous lectures on cognitive neuroscience. Her vision is to bridge the gap between academic research and practical implementation of findings across wellbeing in organizations. She also enjoys designing homes, dancing, and aerial silks.

Dr. Aparna Samuel Balasundaram

Dr. Aparna Samuel Balasundaram, is the Global Head for Wellbeing and Resilience, for the Consumer Business for Wipro-iCORE. She successfully built and executed a clinical and evidence-based approach to employee wellbeing and psychological health, incorporating a DEI lens, for this vertical. She is an award winning and published thought leader, TEDx speaker and has over 24 years of experience in mental health and wellbeing, with a domain expertise in Trust and Safety. She has rich experience across corporate and behavioral health care settings, with global training in both management and clinical aspects- University of Pennsylvania, Columbia University, New York University, NIMHANS and TISS, India.

She is also a Lecturer at Columbia University, School of Social Work and makes time to garden and dance.